- Home

- Smith, Jill Eileen

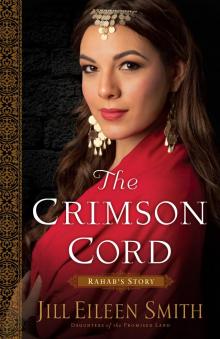

Crimson Cord : Rahab's Story (9781441221155) Page 3

Crimson Cord : Rahab's Story (9781441221155) Read online

Page 3

Rahab studied her sister. How much dare she tell her?

Gamal’s voice cut through the noise of the king’s men, and Rahab quickly stood, Adara with her. “Go home now. Tell Father and our brothers that Gamal has been summoned to the Hall of Justice. I’m going to go with him.” She raised a hand to stop Adara’s protests. “Just go.” She shooed her back the way she had come, then hurried to the gate where Gamal stood arguing with the guards.

“Did you receive the summons from Prince Nahid?” the lead guard asked.

Gamal nodded. “Yes, just this morning. But the first notice said I had three more days. Why this sudden rush and change of plans?”

“And your accounts are ready?”

“I know what is owed.” Gamal’s confidence worried her, but she held her tongue. There was nothing to say to such a lie. The amount owed changed with each new debt he incurred. “But I do not have enough for this month’s payment. I need more time.”

Had he not sold the cloth?

The guard leaned close to smell Gamal’s breath. “And yet you can afford to drink so early in the day?” He shook his head. “The crown prince of Jericho requests your presence in the Hall of Justice. Now.” The two guards near the door each took a step to the side to allow Gamal to walk between them. “You will come.” The speaker glanced through the gate and caught sight of Rahab. His brow lifted in interest. “This is your wife?”

Gamal looked at Rahab, his expression defiant yet wary. “My wife was not the one summoned.” His voice held little conviction. He limped forward without a backward glance at her, but the guard stopped him, blocking his path.

“Your wife will also come.” His command brooked no argument, and Rahab begged the moon god Yerach, and whatever other god might be listening, to keep her husband’s mouth shut. Better she go along than for Gamal to get himself in greater trouble by showing disrespect to the prince’s guard.

Gamal stood fidgeting while Rahab grabbed her cloak from a peg by the door and hurried after them. She ducked her head toward the guard, then walked behind her husband in silence.

The columned hall where the guards led them stood at the front of the debtors’ prison, where men slept when they were loaned out to work the king’s fields or flocks or quarries or worse. Some stayed only long enough to be sold to passing merchants, if the debt was high enough or worthy enough to command such measures.

Rahab leaned against a tall marble pillar at the back of the audience chamber, clinging to her cloak, cinching her scarf tighter at the neck to cover her bruised face. A warm, late spring breeze moved through the open windows to stir the room’s still air, but Rahab felt only the chill of fear as she watched the guards grip Gamal’s forearms and force him to his knees in front of Prince Nahid, seated on a chair of ornate wood and gold. His formal dress of rich robes and the golden circlet crown on his dark head worried her. This prince had power. Would he use it against her husband, against her?

Behind the prince and to his right stood Dabir, dressed in all his royal finery. His presence here should have comforted, but his expression toward Gamal only added to her fear. And her guilt. If she hadn’t given herself to him, would Gamal have been called here three days early?

Her stomach twisted like a wound spindle as the guard who had led them here stepped forward.

“Gamal, son of Bakri, awaits your judgment, my lord,” he said.

Prince Nahid rested both hands on the carved arms of his chair and looked down at Gamal, who still knelt, head bent toward the shining mosaic tiles, his shoulders slumped. In that moment, Rahab wanted to rush forward and pull him into her arms and, for the second time that day, beg his forgiveness for believing Dabir’s honeyed words. To assure her husband that she would never desert him, that things would work out.

But Dabir’s glare held her shivering where she stood.

“Gamal, my friend.” The prince’s tone held surprising kindness. “Have you brought the records of your accounts?”

Gamal did not look up. “I am afraid, my lord, that my accounts are not in proper order. I need time—”

“You have had three years, Gamal. And my records show that your debt is clearly out of hand.” The prince drummed the fingers of his left hand on the chair’s arm.

“Forgive me, my lord, but I fear the injuries to my leg have affected my thinking. The daily pain . . . Sometimes the drink helps, sometimes it clouds my judgment.” Gamal looked up then, and Rahab caught a glimpse of him wincing as he clutched his bad leg with one hand. Irritation pricked her. He was lying. Gamal rarely complained about the pain, and sometimes the limp barely showed. The only thing clouding his judgment was his own lack of common sense and arrogant pride.

“Your judgment is more than a little clouded, Gamal. You owe the king’s coffers nearly twenty years’ worth of silver. Twenty years, Gamal. My life is not worth that much.” Prince Nahid’s heavy brows furrowed, and the grim set to his square jaw revealed age lines along the corners of his mouth. He was still young, probably in his late twenties, a handsome man.

Gamal rose up on one knee and boldly met the prince’s gaze. “On the contrary, my prince. Your life is worth far more. Your father thought so when he offered me such generous gifts after the battle.” The reminder of the king’s reward was aimed precisely as Gamal intended, no doubt. But Rahab saw little warmth in the prince’s eyes.

“I think your memory is also clouded, Gamal. For you have taken my father’s generosity and spent far beyond your means. Your debt to the crown has gone beyond the reward for my life.” He crossed his arms. Rahab held her breath, fearing to release it lest in doing so she lose what little grasp she still had on her self-control.

“Please, my lord, if you just give me more time . . .” Gamal’s voice sounded thin and strained as it lapsed into silence.

“Time is not on your side, Gamal.” The prince cleared his throat. “I am ordering the confiscation of all you own. You will be escorted to debtors’ prison until we can find suitable buyers to take you or until you can work off your debt in the king’s stone quarries. Your wife will be sold as well.”

Rahab stuffed a fist to her mouth, unable to stifle a soft cry, but the sound went unheard as Gamal’s cries rose above hers. He fell to the tile floor, face in his hands, weeping.

“Please, my lord, I beg you, do not hold this thing against your servant. If you will have mercy on me and cancel the debt, I promise I will make it up to you.” His voice broke on a sob as guards stepped closer. They stopped at the prince’s upraised hand. “Please, remember the kindness done to you by your servant, and if you will release me from this bond, I will never again mention the king’s reward in your presence, nor consider myself worthy of anything else from your hand. Only please, have mercy on me!”

Rahab pulled the cloak tighter, clenching her jaw to keep it from trembling. Did the moon god hear the prayers of gamblers begging release from debts they owed? Or was it some other whose amulet she should have purchased who deserved her sacrifice? Her sister would know. Why hadn’t she asked her long ago?

Bile rose in the back of her throat as she watched the prince stare down at her weeping husband. Why did he wait? What point was there to watching a man humiliate himself?

She grew faint as the full force of Prince Nahid’s words hit her. What did it mean to be sold into slavery? What would she do? Who would purchase her? The images in her mind’s eye were not pleasant.

My darling Rahab, you are much too beautiful to be a common harlot. Dabir’s words mocked her now. If she were sold, no one would see her weaving skills worth nearly as much as her beauty.

She moved farther into the shadows, silently cursing the gods for making her desirous to men, suddenly wishing she could fly away like a bird and disappear where no one could find her.

“Stand up, Gamal.”

The command snapped her thoughts to the prince once more.

Gamal rose slowly, using both hands to hold on to his bad leg to gain his balance. He stood

and wiped his eyes, shoulders slumped, head bowed.

Silence descended in the hall as Prince Nahid sat, arms crossed, his gaze raking her husband. What was he doing now? Did the prince enjoy this game of torture?

“I will cancel your debt.” He rested both hands on the arms of the chair. “See to it that you do not squander my mercy.”

The room closed in on Rahab, the breath sucked from every pore as every man stood still, processing the prince’s words. A moment later a gentle breeze returned, touching Rahab’s cheeks, freeing her from the prison of her fear. Had she heard correctly?

Gamal’s weeping returned, and he fell once more to his knees. “Thank you, my lord! You are the greatest of princes. May you live forever!”

“Help him up and take him home.” Prince Nahid’s lips twitched, but he did not smile, and Rahab did not miss the hint of skepticism in his eyes, nor the complete scowl on Dabir’s square face.

Two guards stepped closer to Gamal and lifted him from the tiles, half carrying him toward the doors near where she waited. He met her gaze as they approached, his expression a mixture of relief and something she could not define. If she did not know better, she might think Gamal thought everything had turned out exactly as he’d planned.

3

Rahab stood at the bronze kettle set over the fire, dipping her spun thread into the red dye. She had spent yesterday with her sister, gathering poppies for the scarlet color, as she could not find enough crimson worms to produce the color in large amounts. Poppies weren’t nearly as rich a shade, but the yellow anemones for the golden threads winding through the garments should add to the color’s lack.

A sigh lifted her chest, and she tightened the scarf over her nose to mask the smell of the dye combined with the leftover scent of the retted, drying flax coming from the roof. Weaving had its happier moments, but these were not her favorites. Her only consolation came in knowing she could provide food for their table, to feed Gamal’s belly, even if she could not console his moods. She watched him from the corner of her eye, a caged mountain goat, always butting his head where it didn’t belong.

“I’m going out,” he said after his third look into the pot that held the dye. He scrunched his face and whirled about, no sign of his limp, and stomped toward the gate. “I’ll be back in time to break bread.”

He slammed the gate and turned toward the center of town. Toward the gaming houses. Did this city never sleep? The seedier businesses stayed open long past the sun’s setting and opened shortly after dawn. If a man wanted to drown his worries in barley beer or strong drink, they were more than happy to comply.

She turned from stirring the dye once more to step into the house, away from the sun’s glaring heat. Gamal had known not a moment’s peace in the week since the prince’s pardon.

If he was not careful, he would ruin everything.

“Rahab?” She startled at the sound of Gamal’s voice. Back so soon?

She hurried from the house to the courtyard and met him near the gate.

“Is something wrong, my lord?” She glanced at the bubbling dye and grabbed the stick to stir it once more.

He snatched his staff from where he had left it leaning against the wall. He couldn’t very well pretend to limp without it.

“I need silver. Where did you put the coins you earned from your last sale of these things?” He pointed to the loom in the opposite corner, where a wide swath of cloth stood partially finished.

“I spent it on food and on flax to make more linen and baskets. I gave you the rest last month.” As much as she would tell him of it.

His nostrils flared with thinly veiled anger. He walked into the house, stomping about, moving furniture, rummaging through their things. There was nothing left worth selling. He had already bartered away their wedding gifts, and though he won a few gambling matches now and then, he would lose even more the next night, always digging his hole and theirs a little deeper.

Please, don’t let him look under the mat. She had taken to offering silent prayers to the air around her. For though the moon god had apparently freed Gamal from the prince’s anger, he had not changed Gamal. Her husband was as difficult as he’d ever been, all gratitude lost within the first day of his reprieve.

Gamal’s curses reached her ears. She poked the wooden prong into the bubbling dye again and lifted the threads. Satisfied with the shade of crimson, she carefully pulled the dyed flaxen threads out of the simmering pot and placed them in a similar pot of tepid water to cool. The tapping of Gamal’s staff stopped behind her.

“When will you be done with that? How soon until you can sell more of it?” His desperate tone revived the worry she had unsuccessfully laid aside. She lifted the last of the fiber into the cooling pot.

“Why do you need silver so badly, Gamal? Our debt is canceled and we have food to eat and a house to live in.” She straightened, facing him. “We have each other. What more do we need?” She gentled her tone, but a chill worked through her at his suddenly charming smile.

He took a step closer and reached for her hand. “A man wants to provide well for his family.” His gaze swept over her, and the flicker of sudden longing filled his gaze. He hadn’t forgotten a man’s need for sons, but the reminder only added to her ever-increasing guilt. “And this house is too small.”

She stared at him, but words failed her. She had failed him. To remind him that they did not need a bigger house for two people would be to remind him of her worthlessness.

He leaned close to her ear. “Did you not see the grand columns of the king’s halls? Why can’t a man like me, a man who saved the prince’s life, be afforded similar pleasures? We deserve more, Rahab, and after I convinced Nahid to cancel the debt, I knew the gods were smiling on us again.”

Cold fear shook Rahab, though the heat of the fire and warmth of the midday sun made beads of sweat break out on her forehead. She met Gamal’s gaze, pulled her hand from his grasp, and wrapped her arms about her. “No . . . it isn’t right.” Her words, a mere whisper, were not lost on Gamal.

“Of course it’s right.” He took a step away from her, his glare piercing. “Why don’t you ever believe in me, Rahab? No man always wins at the tables, but some have made enough to buy their wives jewels and build bigger houses on King’s Row. I can finally do the same for you, and you throw it back in my face?” The pitch of his voice rose with his ire, every word punctuated.

She stole a look at him again, holding herself slightly away, afraid he would slap her. But he whirled about, slamming his staff against the stones as he walked toward the gate instead. “I will get the silver, Rahab, and make my fortune.” He threw a look over his shoulder. “You’ll see.”

Rahab stumbled over to a nearby bench and sank down, huddling beneath the shelter of her own crossed arms and hooded veil. How could Gamal not see the dangerous end to his plans? Had Prince Nahid’s mercy meant nothing at all to him?

She watched him pass through the gate, his curses lingering in his wake.

Tendaji hefted a sack of newly threshed wheat over his shoulder, forcing himself to be grateful for such an abundant harvest. Sweat from the afternoon’s heat still glistened on his skin, and the weight of the sickle hung from his belt. But his mother would eat and that was good. Please, let her eat.

When she was gone, he would stop caring.

If only Kahiru had lived.

He fought the urge to shake his fist at the sky. The moon god did not care about a Nubian’s grief. Most of the people of Jericho had little use for him or his family, especially since Kahiru had been lost in childbirth, taking their son with her. Kahiru, a Jericho-born Canaanite, had not cared about the color of Tendaji’s dark skin. She had cared about him, had loved his family, especially his mother.

He swallowed the grief, hefting the sack to his other shoulder. She’d been so small, so beautiful. What had she ever seen in him, big brute that he was? He sighed at the memories, the harsh, blaming looks that followed her death. As if he had someh

ow caused it.

And now his mother had succumbed, had let the grief of too much loss fill her belly in place of food. Perhaps there was only so much pain a body could hold and still breathe.

He had seen too much pain.

Kahiru’s face filled his mind’s eye, though it did not linger. The memories were fading with each passing year . . . Their son would have been walking by now. And had he lived, Tendaji would have taken him often to the fields to learn to handle the bow and arrows. As all Nubian boys learned long before they truly became men.

He glanced at the half moon not yet fully visible in the fading sunlight and nearly spat in the moon’s face. What good were prayers unanswered? What use a god who did not hear?

He rounded a bend leading to a small house on the farthest edge of town, struck by its crumbling mud-brick walls. Weariness made every muscle weak as he dumped the sack onto the cracked courtyard stones and sank onto the bench, wondering if it too would betray him and give way under his weight. A clay basin leaned against the wall, and tepid, brackish water sat in a cistern for him to wash his feet. He closed his eyes, imagining for the briefest moment what it would be like to have someone else care for his needs.

To have Kahiru back again.

A hobble-clop coming from the street drew him up short. He straightened and stood, turning away from the sound. No one would intentionally visit him here.

But the thumping clop of a limping man made him turn again toward the courtyard. “Gamal?” He blinked, certain he was mistaken.

“It is I, as you can see.” He came closer and stopped.

“What brings you to my humble home, Gamal?” Wariness filled him. He had not seen Gamal since the war. Only his wife had come to pay her respects when Kahiru abandoned him to Sheol. “Won’t you sit and take your rest?” His courtesy won over caution as he motioned to one of two benches that circled a cold hearth at the edge of the small court.

“I have not come to visit.” Gamal’s tone was hard, and the light from the setting sun bathed his face in shadow. Tendaji felt the skin on his neck prickle. Gamal was a friend. He relaxed his stance.

Crimson Cord : Rahab's Story (9781441221155)

Crimson Cord : Rahab's Story (9781441221155)